You'd be hard-pressed to find a publication more scrutinized than Pitchfork.

They made their name as self-professed tastemakers, praising and panning albums to ridiculous extremes, shaping the modern indie rock scene almost at will, wielding their absurdly overwrought reviews without an ounce of self-doubt or journalistic integrity.

As the company expanded, the absurd hyperbole that marked the majority of their early reviews ("I had never seen a shooting star before") was largely abandoned, their youthful exuberance replaced instead with the poised indifference of an aging kingmaker with nothing left to prove. In a neat little "jumping the shark" moment, writer Sean Fennessey used the term "post-dubstep" in his 2010 review of Plastic Beach, only to have editors remove it from the article almost immediately. The times had clearly changed.

Yet even as their reviews became more levelheaded and mature, Pitchfork's most defining and most toxic characteristic continued on, perhaps growing even worse over time: the "set 'em up, knock 'em down" hype cycle.

There is no better example of this process than Tokyo Police Club.

They emerged from a burgeoning Canadian indie rock scene in April 2006 with A Lesson in Crime, an EP of catchy synth-driven tunes that actually managed to break into the Canadian top 200. Pitchfork gave it a 7.9 rating in August, noting in their review that Tokyo Police Club was already "blogger-approved," their four-month stint in the hype machine rendering them veterans of a world where a single show can make or break a rising act.

From there, the fuse was lit. Those six brief songs circulated at astounding speeds, gathering so much attention that even dinosaurs like Rolling Stone took notice. The "next-big-thing" label had been officially applied, and the music world waited anxiously for the mindblowing follow-up to their opening statement.

Of course, that mindblowing follow-up never came. They released the decent-enough Smith EP in 2007, which fueled anticipation even further, while notably adding nothing to the formula of their debut. Yet even with the increasing evidence that Tokyo Police Club was never going to advance beyond "Nature of the Experiment," the hype continued, the game-changing full-length lurking forever on the horizon.

By the time Elephant Shell was released in 2008, Tokyo Police Club were a bunch of has-beens. Pitchfork had moved on to a new batch of indie darlings (Vampire Weekend! Fleet Foxes! Crystal Castles!) who were not only more interesting, but also objectively better.

After two long years, there was virtually nothing the band could do to fulfill the promises that had been lined up for them. So, when their first LP turned out to be another batch of decent indie rock songs--which was all they had ever really made in the first place--they received a tame 6.3, banishing them to the well of middling artists that would continue to receive middling reviews as long as they put out middling records, a fate arguably worse than being panned outright. (Their follow-up, Champ, actually received a 7.6, but don't be fooled: anything less than an 8 is still a noteless "meh.")

All things considered, Tokyo Police Club emerged from the belly of the beast more unscathed than most. (When's the last time you've heard Tapes 'n Tapes mentioned by anyone?) They're still putting out albums, they're still touring, and they've graduated to a level of popular recognition that even granted them an opening spot for indie-pop giants Foster the People. They never met their media-assigned potential, but ultimately that's the real point of the hype machine: setting up impossible expectations, only to trash anything that falls short. There's nothing particularly wrong with Elephant Shell, but thanks to the hype machine, it will forever be remembered for not being A Lesson in Crime, Part Two.

Friday, May 31, 2013

Thursday, May 30, 2013

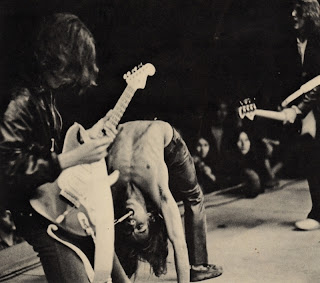

the stooges - fun house

1970.

Just one year after Woodstock.

The very year the Beatles broke up.

One year before David Johansen joined the New York Dolls.

Four years before Douglas Colvin became Dee Dee Ramone.

Sid Vicious was 13 years old.

---

The Stooges have always been a band out of time.

They dressed like hippies and played music heavier than death itself, emerging from the frat rock haze of Ann Arbor with a sound that was arguably more revolutionary than anything that had come before it. Iggy Pop dominated a stage like a man possessed, taking audience confrontation to unheard of levels, injecting waves of violence into his act that would have made Jim Morrison cringe, and setting a standard for rock frontmen that has never been equaled. The Asheton brothers and Dave Alexander took the raw, primal energy of American garage rock, infused it with an acid-fried psychedelic edge, and created a frighteningly original sound that soared past the traditional blues-worship roots of "rock 'n roll" into something completely, truly unique, dangerous even, fulfilling the promise of a decade of forward-thinking 60's musicians as they worked to demolish everything that decade had stood for.

The world got a brief glimpse of their potential on The Stooges, when John Cale's ego subsided enough to let their sound shine through, but Fun House was where they truly hit their stride.

It's a preposterously great rock album. It also marks the last time the Stooges were really "the Stooges." The band behind Raw Power was a different beast altogether: Dave had drank himself into oblivion, Ron had been unceremoniously recruited as a lowly bass player, James Williamson had taken over on lead guitar, and Iggy Pop was loaded to the brim with fame, notoriety, drug use, and an increasing need to live up to the character that was quickly taking him under.

Raw Power was "Iggy & the Stooges," a glorified vehicle for Iggy that David Bowie kept from self-destructing just long enough to drag an album kicking and screaming from its churning depths.

Fun House was pure Stooges from beginning to end, and for me marks the high points of both the band and Iggy Pop's entire career. One howling, monstrous song after another, pierced by Ron's wah-wah outbursts and Iggy's relentless antagonism, finally culminating in "L.A. Blues," a piece that stands as an early noise rock masterpiece, or an obnoxious belch of sound with no merit whatsoever, depending on your temperament. Either way, it's undeniably a perfectly chaotic closer to an album that constantly sounds like it's about to fly off the rails.

If Altamont really did hail the end of 60's idealism, the soundtrack to its violent demise sure wasn't the Stones--it was "L.A. Blues," Fun House, and the Stooges. Fuck that sentimental rock writer bullshit, I'll take my hippie catharsis as gleefully violent as I can get it. Hold the downers, load me up on the feedback, all night till I blow away. Let's ride this fucker straight to hell where it belongs.

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

jimmy eat world - clarity

"Emo" occupies a strange, twisted place in my heart.

I grew up hearing the word emo both as a term of derision and a legitimate descriptor of a musical sub-genre. Neither meaning was concrete by any means, and they often seemed to vary between social groups, or even individual people. Eventually, emo simply devolved into a catch-all term to mean whatever you wanted it to, positive or negative--not unlike what "indie" would soon become.

As I got older and started to branch out musically, however, I slowly began associating emo solely with "emocore," a derivative brand of hardcore punk that favored sincerity and revealing, personal lyrics over political leanings or simple raw aggression.

At its roots, emocore really didn't differ all that much from hardcore. To me, Rites of Spring never really sounded all that different from any other Dischord band. The genre arguably only began to take shape when bands took the style in a more pop-oriented direction, breaking most directly with Sunny Day Real Estate. Certainly for me, emo only became a tangible force upon hearing Diary and LP2.

I keep waiting to grow out of this music. I've definitely reached a point where my heart is no longer worn so openly on my sleeve, and in that sense it has grown harder and harder to relate to bands like Sunny Day Real Estate or Mineral or Cap'n Jazz or their endless streams of imitators. Yet I keep finding myself listening to them, perhaps not with the same youthful fervor, but nonetheless with at a level of interest that transcends simple nostalgia.

I guess the simple answer is that this is music for unhappy people, and I am an unhappy person. But I no longer have that angst inside me, the kind of yelping passion and feeling of being wronged or what have you that drove my initial connection to emo. The flames have dulled to a few burning embers, the almost violent desire for fulfillment reduced to an uneasy acceptance of my life situation. I suppose you could call it maturity.

Yet here I am, listening to Clarity for the umpteenth time, an album dated to the point that the very people making it aged out of the genre almost a decade ago. Is it an amazing listen? Not particularly. The impassioned delivery is certainly compelling, and "A Sunday" has always been one of my favorite songs, but much of it settles into the kind of pleasant, vaguely alternative lull that Jimmy Eat World has based their career on.

So why am I listening to it? Am I trying to reclaim those high school emotions? Am I trying to relight the embers? Or am I just too tied down to the music to let it go?

Perhaps I'm just overthinking it all. As "Goodbye Sky Harbor" spirals on into its ninth minute, I'm not finding myself thinking back to high school or college or lost loves, or really anything at all. It's pleasant music that resonates somewhere within me as an honest emotional release. Which is all "emo" should really be in the first place.

I grew up hearing the word emo both as a term of derision and a legitimate descriptor of a musical sub-genre. Neither meaning was concrete by any means, and they often seemed to vary between social groups, or even individual people. Eventually, emo simply devolved into a catch-all term to mean whatever you wanted it to, positive or negative--not unlike what "indie" would soon become.

As I got older and started to branch out musically, however, I slowly began associating emo solely with "emocore," a derivative brand of hardcore punk that favored sincerity and revealing, personal lyrics over political leanings or simple raw aggression.

At its roots, emocore really didn't differ all that much from hardcore. To me, Rites of Spring never really sounded all that different from any other Dischord band. The genre arguably only began to take shape when bands took the style in a more pop-oriented direction, breaking most directly with Sunny Day Real Estate. Certainly for me, emo only became a tangible force upon hearing Diary and LP2.

I keep waiting to grow out of this music. I've definitely reached a point where my heart is no longer worn so openly on my sleeve, and in that sense it has grown harder and harder to relate to bands like Sunny Day Real Estate or Mineral or Cap'n Jazz or their endless streams of imitators. Yet I keep finding myself listening to them, perhaps not with the same youthful fervor, but nonetheless with at a level of interest that transcends simple nostalgia.

I guess the simple answer is that this is music for unhappy people, and I am an unhappy person. But I no longer have that angst inside me, the kind of yelping passion and feeling of being wronged or what have you that drove my initial connection to emo. The flames have dulled to a few burning embers, the almost violent desire for fulfillment reduced to an uneasy acceptance of my life situation. I suppose you could call it maturity.

Yet here I am, listening to Clarity for the umpteenth time, an album dated to the point that the very people making it aged out of the genre almost a decade ago. Is it an amazing listen? Not particularly. The impassioned delivery is certainly compelling, and "A Sunday" has always been one of my favorite songs, but much of it settles into the kind of pleasant, vaguely alternative lull that Jimmy Eat World has based their career on.

So why am I listening to it? Am I trying to reclaim those high school emotions? Am I trying to relight the embers? Or am I just too tied down to the music to let it go?

Perhaps I'm just overthinking it all. As "Goodbye Sky Harbor" spirals on into its ninth minute, I'm not finding myself thinking back to high school or college or lost loves, or really anything at all. It's pleasant music that resonates somewhere within me as an honest emotional release. Which is all "emo" should really be in the first place.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)